Ursula and I made a recent stop at my favorite local gun store, Collector’s Gun Exchange. As I was perusing the shop, focusing mainly upon the more collectible firearms, salesman Cameron was playing around with a neat little pistol that had just arrived a very few hours earlier. He handed it over to me and asked what I thought of it. My first impression upon feeling the weight and noting the diminutive size was, is this a .22? Nope. It was the new Smith and Wesson Bodyguard 2.0, which comes chambered in .380 ACP/9mm kurz. I was immediately impressed. And when Cameron pointed out to me that this striker-fired elf came with a manual thumb safety, I was pretty much sold.

And then I tried the trigger. Smooth, and light. Lighter than even my Sig P365 SAS (which I modified to include a manual safety), which I’ve carried for five years now, but not as good as the single-action mode on my previous carry weapon, the incomparabe Walther P99c AS. My only minor quibble was the longish takeup, about 5mm, with the reset coming in at about the same. More on the trigger later.

It’s nice that Smith and Wesson includes both a 10-round and 12-round magazine. It would be even better if S&W included a second 12-rounder for a total of three magazines, but since Sig Sauer only gave me two 10-rounders with the P365 I guess I’m not going to complain.

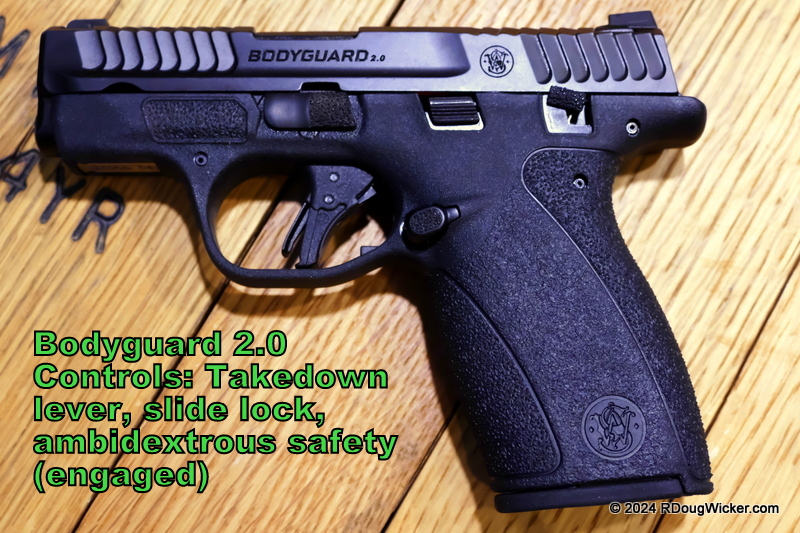

The Bodyguard 2.0 comes in two flavors — Rocky Road and Strawberry Cheesecake. No, wait. I’m thinking of something else. The Bodyguard 2.0 flavors are TS and NTS. The Bodyguard 2.0 TS is equipped with an ambidextrous Thumb Safety, and the NTS has No Thumb Safety. When it comes to a carry weapon, I’m all about the safety. All my carry pieces are either double-action/single-action, have a manual safety, or both. Holding the Bodyguard in my right had, I have no trouble disengaging or re-engaging the safety. Switching to the left hand did not go as smoothly for some reason. Unless my left thumb is drastically weaker than my right, which I doubt, this thing is just darn sticky on the starboard side of the firearm. I’ve been working the safety a bit, and it seems to be smoothing out.

Now back to the trigger. It’s a flat-face, which seems to be the current rage. And it does seem to assist somewhat in keeping a consistent pull. I rather like it. The pull weight is defintely nice, as well. A five-pull average on my trusty Lyman Digital Guage shows 4 pounds 3.6 ounces/1,915 grams. That certainly beats the P365, which comes in at 6 pounds 8.7 ounces/2,969 grams. For an additional comparison, the AS trigger on the Walther P99 was advertised as 4.4 pounds/2kg in single-action and exactly twice that in double-action. So, the P99’s single-action pretty much matches the Bodyguard’s pull weight.

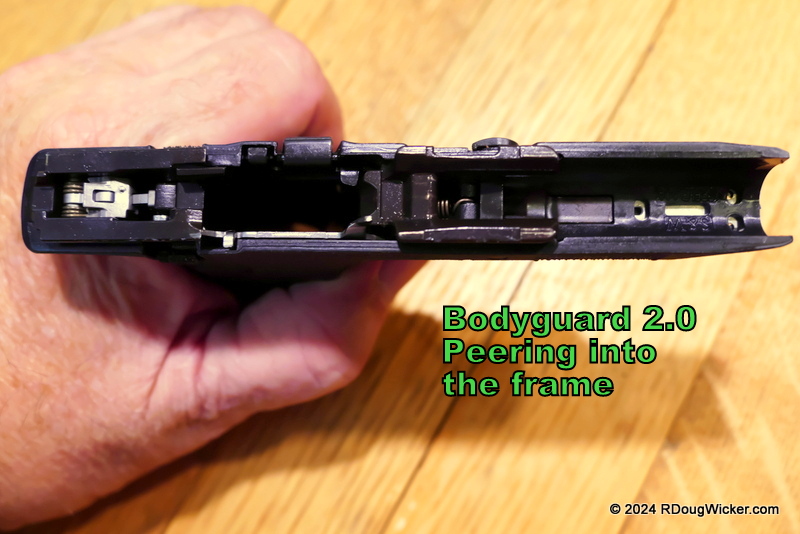

The Bodyguard’s takedown and reassembly beats the P365 hands down, but that’s because the SAS variant of the P365 swaps out an actual lever for a difficult-to-manipulate slotted head. One word of caution on taking down the Bodyguard: with the slide locked back, depress the ejector all the way down. It’s even more important to make sure the ejector is down before reinstalling the slide. Failure to do so will potentially snag the ejector and possibly damage it.

To raise the ejector after reassembly, simply insert an empty magazine. If you don’t raise the ejector, the trigger will not engage the striker and you will be unable to function-check the firearm after getting it back together.

After removing the slide, everything else is a snap. Compress the guide rod and lift away from the barrel lug, then remove the barrel:

Reassembly is not quite as easy. I had a dickens of a time reinstalling the guide rod. The darn spring just refused to compress. It was almost as if the spring was binding at the forward end of the rod when I placed it into the slide guide rod cutout. Several attempts to remove the guide rod and compress the spring with my fingers, and later a flathead screwdriver, took quite a bit of effort. But after repeated attempts I got the spring to move, and eventually got the guide rod back in, compressed, and reseated onto the barrel lug. I suspect I may have a faulty spring, but once I got it back in there was no binding.

The sights are a bit like a Spaghetti Western — There’s the good, the bad, and the ugly. The good is that the front sight is tritium with a high-visibility orange surround. The bad are that the tritium portion is very tiny. The ugly is the absolutely hideous U-notch rear sight — all black with no side indices for low-light acquisition and a ridiculously wide notch. There will be no match shooting with this handgun. But, then again, that’s not why it exists. Inside of 25 yards/23.8 meters I doubt I’ll have problems keeping on paper. I may not be as accurate in the dark, however. There’s simply no way to tell if I have the front sight within the notch, let alone have it centered left, right, up, or down. That’s certainly a minus in comparison with the P365’s Mepro FT Bullseye, even though the FT Bullseye also has its challenges in low-light situations.

So, am I ready to swap out the P365? I think so. I’m definitely going to consider it after I’ve thoroughly checked out the Bodyguard for reliability. It’s smaller, much lighter, and holds the same number of rounds. The only downside is that I’ll be stepping down to .380 ACP/9mm kurz from the more powerful 9mm Luger. But, heck, I’ve even been known on occasion to carry .32 ACP/6.35 mm in a Beretta 3032 Tomcat or a Walther PPK and still not feel insufficiently armed.

I mentioned a moment ago that the S&W Bodyguard is considerably lighter than the Sig Sauer P365 SAS. I measured them today, both with empty 10-round magazines inserted. The P365 weighs 17.88 ounces/507 grams while the Bodyguard is a featherweight 11.48 ounces/326 grams.

S&W Bodyguard 2.0 TS Dimensions and Other Information:

- Length: 5.5 inches/140mm

- Height (with 10-round magazine): 4 inches/102mm

- Width: 0.88 inches/22mm

- Barrel length: 2.75 inches/70mm

- Weight (with empty 10-round magazine): 11.48 ounces/326 grams

- Capacity: 10+1 and 12+1 with included magazines

- MSRP: $449

- Street price: $399

Hopefully I’ll get out a range report soon. In the meantime, if you’ve any questions just leave me a comment.

Слава Україні! (Slava Ukraini!)

Decisions — Murder in Paradise

Decisions — Murder in Paradise The Globe — Murder in Luxury

The Globe — Murder in Luxury