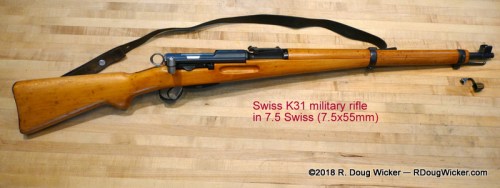

I’ll be returning to my “54 Days at Sea” series next week. Until then, this week is dedicated my most viewed subject — firearms. And today I present an extraordinary one, a Swiss K31 bolt action rifle.

The K31 was the primary weapon of the Swiss Army from 1933 until 1958. So, if that’s the case, why is it called the K31? Because the first rifles were delivered to the Swiss Army for testing in 1931. The K31 is often called a “Schmidt-Rubin” K31, but this isn’t technically correct. The original Rudolph Schmidt straight-pull bolt action design dates back to 1889, and culminated in the K31’s immediate predecessor, the K11. The Eduard Rubin 7.5 “GP90” was the cartridge around which the Model 1889 was designed. This basic rifle/ammo combination lasted through several improved models, but the K31 has little in common with the previous Schmidt rifles beyond the straight-pull concept and the ring-pull cocking piece/safety. The bolt, for one thing, was a near complete redesign and much stronger than the Model 1889 through K11 bolts.

Likewise, the GP11 7.5 x 55mm cartridge is considerably more powerful than the previous Rubin cartridges, despite the similar case and bullet dimensions. The GP11 cartridge propels a 174-grain/11-gram bullet at an impressive (for the time) 2,560 feet per second/780 meters per second, thus attaining a muzzle energy of 2,535 foot-pounds/3,437 joules. To put that in modern terms, the 7.62 x 51 NATO round developed almost a quarter century later propels a nearly identical 175-grain bullet at 2,580 feet per second/790 meters per second for a muzzle energy of 2,586 foot pounds/3,506 joules. In other words, the 1930 GP11 7.5 x 55mm round is pretty much the equal of the 1954 7.62 NATO, which is still in use by the U.S. military today!

Now for that previously mentioned ‘straight-pull’ bolt action. Most bolt action rifles, including K31 military contemporaries such as the German Mauser Karabiner 98 kurz (K98k), require four movements to eject a spent casing and chamber a fresh round:

- Lift up on the bolt handle, thus rotating and unlocking the bolt

- Pull back on the bolt handle to extract and then eject the spent casing

- Push forward on the bolt handle to strip a fresh cartridge from the magazine and force it into the chamber

- Lower the bolt handle to rotate and lock the bolt

The K31 and its predecessors got this down to just two movements:

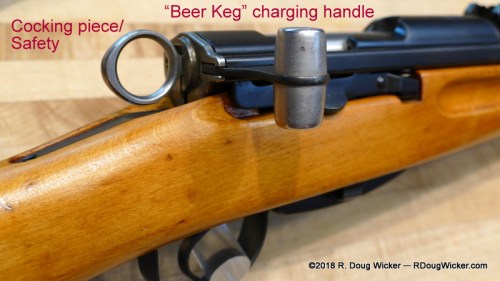

- Pull back on the ‘beer keg’ charging handle

- Push forward on the charging handle

Because of the bolt design, pulling back on the charging handle causes the bolt to simultaneously rotate and unlock.

As the handle is brought farther back, the spent casing is extracted from the chamber and ejected from the weapon. Pushing forward strips a round from the magazine, forces it into the chamber, and rotates the bolt into the locked position.

The magazine also acts as a lock-back when empty. The follower of an empty magazine will block the bolt from being pushed forward. This feature warned the soldier that it was time to reload. To push the bolt home again, either remove the magazine; or place your thumb into the ejection port and push down on the follower while pushing forward on the charging handle until the bolt rides over the rear portion of the follower. Then extract your thumb and continue pushing the charging handle forward until the bolt rotates back into the firing position.

The large ring you see protruding from the back of the bolt is yet another feature. This is the cocking piece. When the ring is vertical and resting against the bolt then the firing pin is not cocked.

If the ring is vertical and protrudes away from the back of the bolt, then the firing pin is cocked and the weapon is ready to fire.

But, if the cocking piece has been pulled, rotated clockwise, and then recessed back into the bolt, then the weapon has been placed into a ‘safe’ mode. The firing pin is held back away from the cartridge primer.

Pulling the cocking piece back and returning the ring to the vertical position leaves the firing pin cocked and the weapon ready to fire. Likewise, this cocking piece also gives the shooter double-strike capability following a misfire. Simply pulling the ring back about ⅝ of an inch/16mm cocks the firing pin.

Safety note: The cocking piece can be held while the trigger is pulled, and then gently allowed to travel forward to decock the weapon. Do not do this over a chambered round, as there is no ‘half-notch’ or ‘quarter-notch’ safety built into the K31. Once “decocked”, the firing pin can still protrude through the breech face and make contact with the primer. Only use the cocking piece as a decock over an empty chamber.

The K31 has a detachable six-round magazine. The magazine can be removed and manually loaded. This is accomplished as with a .30 M1 Carbine; rounds are simply pressed in from the top, and they stagger automatically is they go into the magazine.

There is, however, a second method of loading the magazine. With the magazine locked into the magazine well and the bolt open, a six-round charging clip can to inserted into the ejection port. The thumb of the right hand then pushes down on the rounds, forcing them into the magazine in one fluid motion. The clip is this removed and tossed aside (the originals were cheap and disposable). Here is a demonstration using an after-market plastic charging clip made specifically for the K31 and the Schmidt-Rubin K11 that preceded the K31:

K31 rifles were issued with small field maintenance kits. These cloth bags, unused examples of which you can readily obtain today, came with two tins containing waffenfett (gun grease), brass pull-through, chamber cleaning tool, and a mirror to check the bore. Waffenfett tins are pretty hard to come by, but the other items were included in the kit I obtained. The supplier also included a plastic charging clip in the price.

Another included piece of equipment, which you can also find online, is a brass muzzle protector that clips in place over the front sight.

A good example of the K31 is one on which all the serial numbers match. This includes the bolt, receiver, stock pieces, other parts, and even the magazine.

The K31 is renowned for its amazing accuracy. This is truly a one MOA (minute-of-angle) weapon, meaning that when properly sighted and with an expert marksman at the trigger, the shot grouping should be no more than one inch across at a range of 100 yards. Looking at the crowned barrel is just one clue as to the inherent accuracy of these weapons.

And then there are the front and rear sights. You shouldn’t ever have to drift the front sight unless somebody fooled around with it after it left the armorer. But if your K31 is hitting left or right of target, the front sight can be adjusted by drifting it forward and backward along a rather unique slanted grove. At the nominal 300-meter/328-yard sighting range for the K31, a 1 millimeter movement of the front blade sight results in a 12-centimeter/4.7-inch change in the point of impact.

Yes, you read that correctly. Each and every K31 was presented to its operator sighted in at an astounding 300 meters. And the size of the target at 300 meters? The requirement was for the shooter to hit with his first shot a 0.2-meter²/2.15-foot² target! No wonder the Germans never invaded Switzerland. Now, let us take a look at the rear sight, which is calibrated for ranges between 100 meters/109 yards and 1,500 meters/1,640 yards (a mile, by the way, is 1,760 yards!):

Sighting on targets is also range-dependent. For instance, at ranges less than 300 meters, the top of the front blade sight is placed at target center. At 300 meters and beyond the target should sight just above the front blade. In other words, at 300 meters and beyond the shooter aims at the bottom of the target.

Expect a firing review of the K31 at a later date.

Some K31 notes for the collector:

- Walnut stocks were used from introduction through the end of World War 2. Beginning in 1946, however, beech was used for the remainder of military production, which ended in 1958. The example in this article was manufactured in 1952, and has a beech stock.

- Military issued K31 rifles had a stiff paper ‘troop tag’ placed beneath the butt plate. These troop tags bore the name and home address of the soldier receiving the rifle, and often his date of birth. I checked, but, alas, no troop tag with this K31.

- While most K31 rifles retain very good bluing, clean bores with well-defined lands and grooves, and are mechanically very sound, the stocks are frequently in very poor condition. These rifles were carried and stacked in snow and mud, and soldiers reportedly would kick the weapon free at the butt using cleated boots. The stock of the example here is in exceptional condition, but that’s the exception to the rule.

- Speaking of stacking, the bent metal piece beneath the barrel is a stacking rod. Three K31 rifles would be stacked in a tripod configuration, using the stacking rods to interlock the weapons to keep them from falling over.

- For collector purposes, all serial numbers should match. For a shooter that’s, of course, less important.

- Swiss Army-issue cleaning kits, muzzle protectors, leather slings, charging clips, and other accessories are readily available online at surprisingly affordable prices. M1918 bayonets with sheaths can also be had, but at upwards of $100 or more for one in good condition.

- Prices can range from $300 for a fair-to-good rifle, to over $1,000 for one in mint condition. However, K31/42 and K31/43 sniper rifles will go for much, much more.

Decisions — Murder in Paradise

Decisions — Murder in Paradise The Globe — Murder in Luxury

The Globe — Murder in Luxury