It’s still “M” Week at the blog, and today’s “M” stands for that classic American maker of lever-action rifles — Marlin.

Yes. It’s true. I have a soft spot for Old West-style firearms, as you may have surmised by now with my numerous articles on them (Winchester Rifles — Part 1; Winchester Rifles — Part 2; The Rifleman’s Rifle; Firearms — Television Westerns from the 1950s; A Tribute to Mike DiMuzio and a Look at the Interarms Rossi M92 in .45 Colt; USFA Rodeo; AWA Peacekeeper). Today we’re going to look at another firearm with roots in the 1800s. It’s a lever-action rifle, but this time it’s neither a Henry nor a Winchester. It’s a Marlin Model 1894C pistol-caliber carbine chambered in .38 Special/.357 Magnum.

Marlin 1894C Particulars:

- Length: 36 inches/91.4 cm

- Barrel Length: 18.5 inches/46.7 cm

- Length of pull: 13.7 inches/34.7 cm

- Weight: 6 pounds, 8.55 ounces (104.55 ounces)/2.96 kg

- Caliber: .38 SPL/.357 Magnum

- Capacity: 9-round tubular magazine

- Trigger pull (measured by author; average of five): 2 pounds, 14.8 ounces/1.328 kilograms

My impressions upon handling the rifle: The lever action is stiff, bordering on mediocre. The rifle appears little to have been very lightly used, so this may be a break-in situation. The 1894C has a superlative, crisp trigger with no take up whatsoever, and it breaks consistently at just under three pounds. The crossbolt safety (if you’re into such things on a lever action) is easy to manipulate, positively blocks the hammer, and allows for safe decocking of the rifle. I may very well decide to take the Marlin out to the range and compare it against my Rossi R92 (Winchester Model 1892 clone) in the same caliber.

A little history on Marlin and the Model 1894: John Marlin founded the Marlin Fire Arms Company in 1870 in New Haven Connecticut (the company would in 1968 move to nearby North Haven). In 1881 Marlin expanded from single-shot rifles into the lever-action market, and in 1888 Marlin engineer Lewis Lobdon “L.L.” Hepburn revolutionized the concept with a lever-action rifle that ejected cartridges through the side of the receiver rather than via the top.

In 1893 Mr. Hepburn continued to improve and strengthen his design, resulting in two new rifles — the Marlin Models 1894 and 1895. The Model 1894 with its solid-top/side-eject concept was an immediate hit in cold inclement environments such as Alaska and Canada, as the absence of an open-top ejection port prevented snow, rain, leaves, dirt, and other contaminants from dropping into the rifle. The design had the added benefit of being much stronger than the competing Winchester designs of the era.

The Model 1894 differs from Marlin’s Model 1895 in that the 1894 is chambered in pistol calibers, while the 1895 was designed for more powerful rifle cartridges. In the Winchester world, it would be like comparing a Winchester Model 1892 (pistol calibers) to a Winchester Model 1894 (rifle rounds — although some past 1894 rifles were chambered in .44 Rem Mag and other pistol calibers).

As a quick aside, today’s Model 1895 rifle is not quite the same as the original, which was discontinued in 1917. The reintroduction of the Model 1895 name in 1972 is based upon the Marlin 336 rifle dating from 1936, which further improved upon Mr. Hepburn’s 1893 developments.

Marlin’s history has been a bit convoluted since 2007. It was in that year that Marlin fell into the evil clutches of the equity firm Cerebrus Capital Management via their holding company Freedom Group. Freedom Group would eventually try to hide this evil nature by changing its name to Remington Outdoor Group. But true to form, Remington collapsed into bankruptcy last year, taking with it Marlin, which had already been mismanaged into oblivion beginning in 2008 (more on that shortly).

We’ve seen this scenario playout before with the iconic American brand Colt’s Manufacturing and Colt Defense. Then we have Winchester Repeating Arms Company; lever-action rifles bearing the Winchester brand are now manufactured in Japan. Yes, I despise predatory equity management firms, and I feel that’s with good reason.

Fortunately, Remington’s recent (and entirely too predictable) bankruptcy has resulted in Marlin coming under the umbrella of my favorite U.S. firearms company — Sturm, Ruger & Co. If anyone can rescue and restore this historic brand, it’ll be Ruger.

On an unrelated side note: we can all breathe easier knowing that Colt’s Manufacturing now belongs to Česká zbrojovka Group (Czech armory Group — CZG), a company that understands the firearms business. It would have been better in my view if Colt had remained an entirely U.S. company, but at least this way Colt shall survive and prosper.

So, what has all this to do with a Marlin 1894C that dates to 2009? A lot if you’re a collector. Remington (a.k.a., Freedom Group, a.k.a., Cerebrus Capital Management) purchased Marlin in 2007, and took over both ownership and management the following year. Production initially continued at Marlin’s North Haven, Connecticut plant, using experienced Marlin craftsmen who understood the designs they were handcrafting, and who collectively had generations of experience among them.

Marlin’s workers were also unionized. See where this is going now? Yep. In March 2010 Remington announced it would be closing Marlin’s historic North Haven plant, ending 141 years of continuity and experience. In April the following year, the Marlin plant was closed. The unionized craftsmen were terminated. The manufacturing equipment for the lever-action line was boxed up and shipped to a Remington facility in Ilion, New York. Manufacture of other Marlin rifles transferred to Remington’s Mayfield, Kentucky facility. And inexperienced, non-unionized workers began misassembling firearms they had no clue how to put together.

Quality collapsed, of course. Marlins went from being coveted rifles to a bad joke, with unsuspecting consumers supplying the punchline. Eventually, Remington employees would start to turn things around a few years later as they gained experience with the nuances of the designs. But Marlin rifles never fully regained the quality they once exhibited, and the reputational damage was by then complete.

Which brings us to today’s Model 1894C. And this is a weird one. The serial number indicates that the rifle was made in 2009. Production continued at the North Haven Marlin plant at least through the end of 2010, with the doors being locked one final time in April 2011. The barrel displays the North Haven roll mark. The fit and finish, particularly the mating of the walnut stocks to the receiver and barrel, scream Marlin quality. So, too, does the deep, rich bluing of the metal on both the barrel and the receiver.

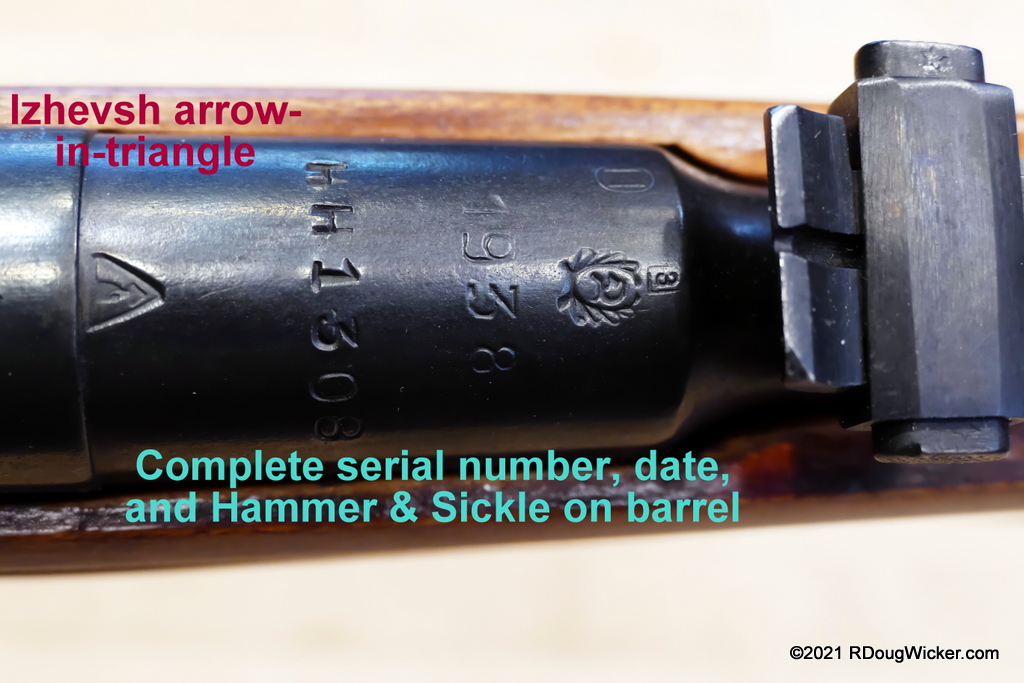

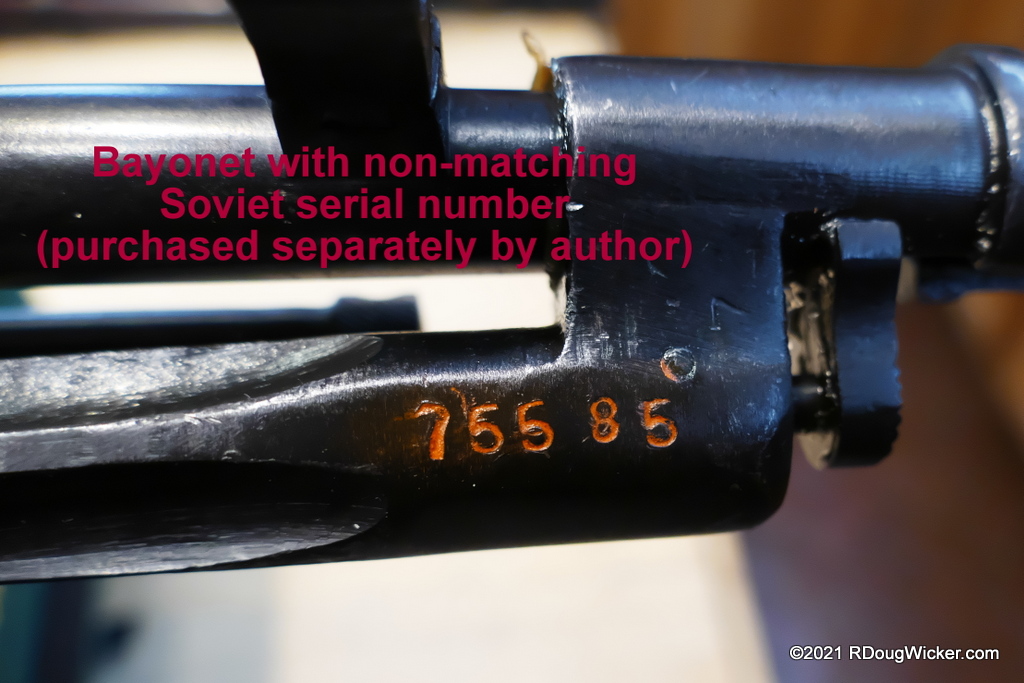

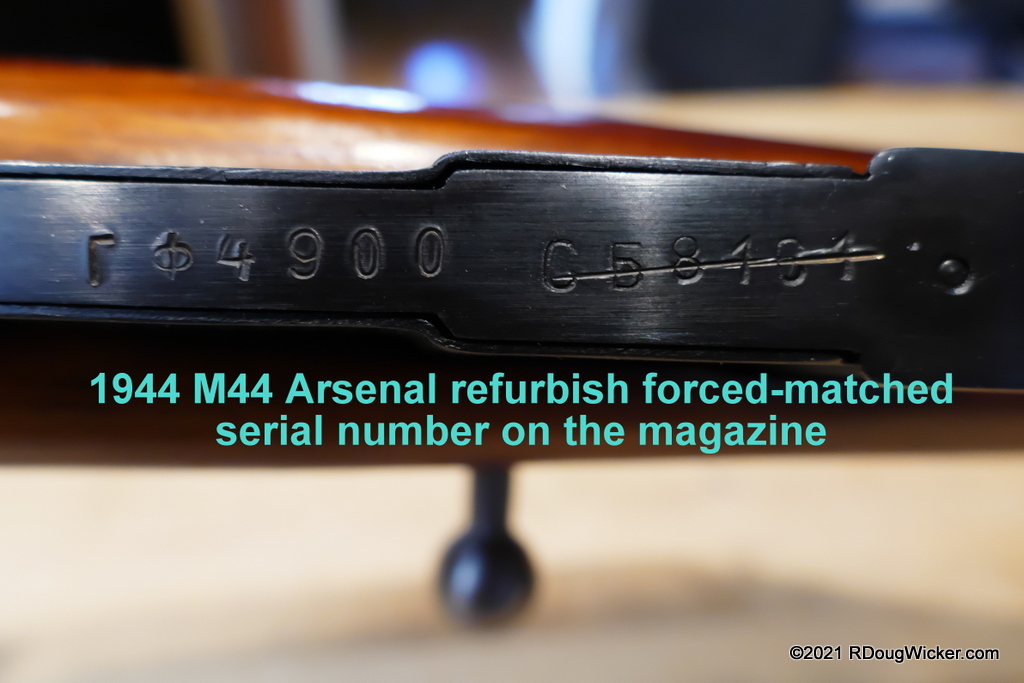

But then there’s the proof mark. If you have a Marlin with a “JW” proof mark, then you have a true Marlin-made Marlin. If your serial number doesn’t start with “RM”, then you have a true Marlin-made Marlin. On the other hand, if you have a Marlin with an “REP” inside an oval-shaped stamp, or the serial number starts with “RM”, then you supposedly have a Remington-made Marlin.

But what if your rifle’s serial number isn’t prefixed with “RM”, the “91” at the beginning of the serial number indicates the rifle was made in 2009, the rifle has a barrel displaying the North Haven roll mark, the fit and finish all give the appearances of a clean, well-made North Haven example, yet your rifle bears the dreaded “REP” on the right side of the barrel? What do you have? Is it a Marlin, a Remlin, a Marlington, or an insidious Remington cleverly disguised as a quality Marlin?

So, what exactly is going on here? Well, there are several possibilities. Toward the end of production, North Haven produced receivers with serial numbers in the “92” (2008) “91” (2009), “90” (2010), and even a few in the “89” (2011) range.

Notes for determining the manufacture date from the serial number:

- For serial numbers starting with 27 through 00, just subtract those first two digits from 2000; example: 2000 – 22 = 1978

- For numbers 99 through 89, subtract the first two digits from 2000 then change the first two numbers in the result from “19” to “20”; example: 2000 – 91 = 1909; change 19 to 20; final result = 2009

- Manufacture dates prior to 1973 used various other schemes)

Sometime in 2011 serial numbers changed from “89” to the “RM” format. “RM” stood for “Remington-Marlin”. Marlin barrels may have changed prior to that, and it appears Ilion still used the North Haven roll mark for a time after Ilion took over at least some of the manufacturing. As to when precisely that occurred, I’ve not been able to discern. Additionally, some North Haven receivers and barrels were shipped to Ilion for final assembly, which would explain very neatly the “REP” on today’s example. There is also the possibility that North Haven sent completed rifles to Ilion, whereupon the “REP” stamp was then applied, but I somehow doubt that is the answer. I believe it’s probably more likely that North Haven transitioned to the “REP” stamp prior to operations moving to Ilion, but I cannot substantiate that as fact.

So, bottom line for the collector:

- “JW” is the proof mark you want for maximum value.

- Pre-crossbolt safety is also a big plus among lever action purists. For that you must get a Marlin made in 1982 or earlier.

- “93” on the serial number (2007 manufacture) gets you out of this who-made-what-when mess altogether. Freedom Arms made the purchase of Marlin that year, but it wasn’t finalized until 2008.

- “92” (2008) means you still definitely have a North Haven rifle, and it most certainly will have a “JW” proof as well. But that’s also the year Remington stepped into the mix. Things started getting dicey, I’m sure, and morale probably started falling at North Haven.

- “91” (2009) — You’re probably still good, but watch out. Hopefully, you have a “JW” proof, but even so quality will be hit-or-miss with the decline in morale. Inspect that prospective acquisition carefully before laying down cash.

- “90” (2010) is the year Freedom Group decided to eviscerate whatever was left of North Haven morale by telling the workforce to train their replacements and prepare for unemployment. At this point any incentive to provide a quality build had long since evaporated.

- “89” (2011) — By now I’m going to say you might as well have an “RM” serial number. Who the heck knows what was going on in North Haven by then?

- “RM” means you’re too late. You may have a shooter, or you may have a major gunsmithing project.

I’m not disappointed in this “91”. Not even close. It appears to be a quality rifle. Most, if not all, the parts are North Haven. I do wish it sported the “JW” proof, and if I knew then what I know now that “REP” stamp might have given me a bit more pause. I balked at the time only because the consignee didn’t bring into the gun shop the original box. He said he didn’t know where it was. I passed to the consignee through the shop owner a low-ball offer for the rifle without the box, and a slightly higher “incentive” offer if he located it. The incentive worked. The owner found the original box and took the latter offer, which was still below his initial asking price.

Decisions — Murder in Paradise

Decisions — Murder in Paradise The Globe — Murder in Luxury

The Globe — Murder in Luxury